Ancient Tang Dynasty War Weapons Ancient Tang Dynasty Art

In ancient China warfare was a ways for one region to proceeds ascendancy over another, for the state to expand and protect its frontiers, and for usurpers to supersede an existing dynasty of rulers. With armies consisting of tens of thousands of soldiers in the first millennium BCE and so hundreds of thousands in the kickoff millennium CE, warfare became more technologically advanced and ever more destructive. Chariots gave mode to cavalry, bows to crossbows and, eventually, arms stones to gunpowder bombs. The Chinese intelligentsia may take frowned upon warfare and those who engaged in it and there were notable periods of relative peace but, equally in almost other ancient societies, for ordinary people it was difficult to escape the insatiable demands of war: either fight or die, be conscripted or enslaved, win somebody else's possessions or lose all of 1's own.

Attitudes to Warfare

The Chinese bronze historic period saw a not bad deal of military competition between city-rulers eager to grab the riches of their neighbours, and there is no doubt that success in this endeavour legitimised reigns and increased the welfare of the victors and their people. Those who did not fight had their possessions taken, their dwellings destroyed and were usually either enslaved or killed. Indeed, much of China'south history thereafter involves wars between one land or another only it is also true that warfare was perhaps a little less glorified in ancient China than it was in other ancient societies.

"No country has always profited from protracted warfare" - Sun-Tzu.

The absence of a glorification of war in China was largely due to the Confucian philosophy and its accompanying literature which stressed the importance of other matters of civil life. Military treatises were written but, otherwise, stirring tales of derring-exercise in boxing and martial themes, in general, are all rarer in Chinese mythology, literature and art than in contemporary western cultures, for example. Even such famous works equally Sun-Tzu'southward The Art of War (5th century BCE) warned that, "No country has ever profited from protracted warfare" (Sawyer, 2007, 159). Generals and aggressive officers studied and memorised the literature on how to win at war only starting from the very top with the emperor, warfare was very often a policy of last resort. The Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) was notable for its expansion, as were some Tang Dynasty emperors (618-907 CE) just, in the chief, a strategy of paying off neighbours with vast tributes of silver and silk, forth with a parallel exportation of "civilising" civilization was seen every bit the all-time way to defend majestic China'due south borders. And then, if war ultimately proved unavoidable, it was better to recruit foreign troops to become on with information technology.

Kuan Ti - God of War

Joining the intellectuals with their disapproval of warfare were also the bureaucrats who had no fourth dimension for uncultured military men. No doubt, too, the vast majority of the Chinese peasantry were never that corking on war either for it was they who had to endure conscription, heavy taxes in kind to pay for costly campaigns, and have their farms invaded and plundered.

With the emperors, the landed gentry, intellectuals and farmers all well-aware of what they could lose in state of war, it was, then, somewhat disappointing for them all that People's republic of china, in any case, had simply equally many conflicts as anywhere else in the globe in sure periods. I cannot ignore the mutual presence of fortifications in the statuary age, such chaotic centuries as the Autumn and Spring Menstruum (722-481 BCE) with its one hundred plus rival states, the Warring States Period (481-221 BCE) with its incredible 358 separate conflicts or the fall of the Han when war was in one case again incessant betwixt rival Chinese states. Northern steppe tribes were as well constantly prodding and poking at Prc'due south borders and emperors were not averse to the odd foreign folly such equally attacking ancient Korea.

Weapons

The great weapon of Chinese warfare throughout its history was the bow. The most mutual weapon of all, skill in its use was as well the most esteemed. Employed since the Neolithic period, the composite version arrived during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) and then became a much more useful and powerful component of an army's assail strategy. Bowmen often opened up the boxing proceedings by firing massed volleys into the enemy and then protected the flanks of the infantry as they avant-garde, or their rear when they retreated. Bowmen too rode in chariots and bows were the main weapon of cavalry.

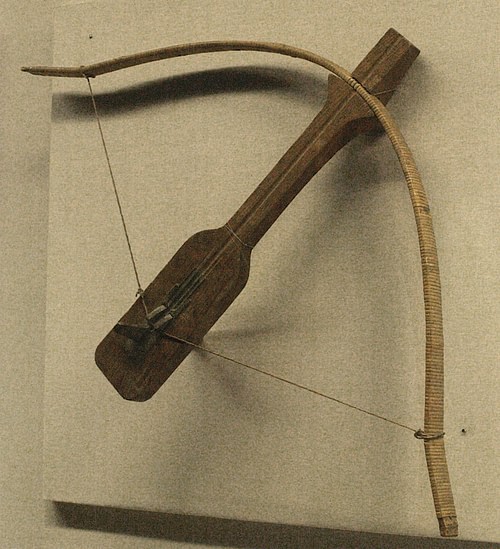

Perhaps the most distinctive and symbolic weapon of Chinese warfare was the crossbow. Introduced during the Warring States Period it prepare China autonomously as a nation capable of technical innovation and the training necessary to use it finer. The Han used information technology to great consequence confronting "barbarian" tribes to expand their empire, their disciplined crossbow corps even seeing off opposing cavalry units. As with bowmen, crossbowmen were usually stationed at the flanks of infantry units. Over the centuries new designs made the crossbow lighter, able to be cocked using one hand, fire multiple bolts and fire them further, more accurately and with more power than before. Artillery versions were adult which could be mounted on a hinge base. Autonomously from its potential as an offensive weapon, the crossbow became a much-used means of defending well-fortified cities.

Qin Dynasty Crossbow

Swords only appeared relatively late on Chinese battlefields, probably from around 500 BCE, and never quite challenged the bow or crossbow as the prestige weapons of Chinese armies. Developing from long-bladed daggers and spearheads which were used for stabbing, the true sword was made from bronze and then, later, iron. During the Han period they became more effective with better metalworking techniques giving stronger blades with sharper cut edges. Other weapons used by Chinese infantry included the e'er-pop halberd (a mix of spear and axe), spears, javelins, daggers, and boxing-axes.

Artillery was present from the Han period when the get-go stone-throwing, single-armed catapults were used. They were probably mostly restricted to siege warfare simply were employed by both attackers and defenders. The more powerful counter-weighted catapult was not used in Communist china until the 13th century CE. Artillery fired stones, missiles made of metal or terra cotta, incendiary bombs using naphtha oil of "Greek fire" (from the 10th century CE) and, from the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 BCE), bombs using gunpowder. The oldest text reference to gunpowder dates to 1044 CE while a silk imprint describes its apply in the ninth century CE (if its dating is authentic). Gunpowder was never fully exploited in aboriginal China and devices using information technology were restricted to missiles made with a soft casing of bamboo or paper which were designed to kickoff fires on impact. The true bomb, which dispersed lethal fragments on explosion, was not seen until the 13th century CE.

Warring States Helmet

Armour

With arrows and crossbow bolts condign ever more lethal, information technology is no surprise that armour made leaps forward in design to meliorate protect warriors. The earliest armour was undoubtedly the nigh impressive - tiger skins, for instance - merely also the least effective and by the Shang Dynasty hardened leather was being worn to encompass the breast and back in a more than serious effort to dampen and deflect blows. By the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) more flexible armour tunics were being produced fabricated of rectangles of tanned and lacquered leather or statuary linked together with hemp or riveted. Examples of this type can be seen in the Qin warriors of the Terracotta regular army of the third century BCE. From the Han period, atomic number 26 was used more and more in armour.

Helmets & armour, on occasion, were busy with plumes, engravings & paintings of fearsome creatures.

Additional protection was provided by shields, the primeval existence made only of bamboo or leather but and then, like body armour, they began to contain metal elements. Helmets followed the same path of material evolution and usually protected the ears and back of the neck. Helmets and armour, on occasion, were decorated with plumes, engravings and paintings of fearsome creatures or beautified with additions in precious metal or ivory. Specialised armour adult for warriors in chariots who did not need to move and then much and could wear full-length armoured coats. There was, too, heavy cavalry where the legs of the rider and the whole equus caballus were protected.

Chariots & Cavalry

Chariots were used in Chinese warfare from around 1250 BCE just were seen in the greatest numbers between the 8th and fifth century BCE. Outset as a commander'due south status symbol and so equally a useful daze weapon, the chariot commonly carried a passenger, bowman and spearman. They were very frequently deployed in groups of 5. Pulled by two, three or 4 horses, they came in unlike versions - low-cal and fast for moving troops effectually the battlefield, heavy bronze and armoured versions for punching holes in enemy ranks, those converted to carry stock-still heavy crossbows, or even towered versions for commanders to improve view the battle proceedings. The chariot corps could also pursue an regular army in retreat. Needing a wide area to turn and flat ground to function, the limitations of chariots meant they were somewhen replaced by cavalry from the 4th century BCE onwards.

Chinese Qin Chariot

Cavalry was probably an innovation from the northern steppe tribes which the Chinese realised offered much more speed and mobility than chariots. The trouble was to larn the skill non only to ride the horses merely also to fire weapons from them when the saddle was not much more than a blanket and the stirrup had notwithstanding to be invented. For these reasons, it was not until the Han period that cavalry became an of import component of a field army. Cavalry riders were armed with a bow, lance, sword or halberd. Like chariots, cavalry was used to protect the flanks and rear of infantry formations, as a shock weapon and as a means to harass an enemy on the motion or deport hit-and-run raids.

Fortifications

Surrounding a settlement with a protective ditch (sometimes flooded to make a moat) dates back to the seventh century BCE millennium BCE in China and the edifice of fortification walls using stale world dates to the late Neolithic period. Siege warfare was not a common occurrence in China, though, until the Zhou Dynasty when warfare entailed the full destruction of the enemy as opposed to just their ground forces. By the Han period, city walls were usually raised to a summit of up to half dozen metres and made of compacted earth. Crenellations, towers and monumental gates were another improver to a urban center's defense force. Walls besides became more than weather resistant by covering the lower parts in stone to withstand local h2o sources being re-directed by an attacking force in social club to undermine the wall. Another technique to strengthen walls was to mix in pottery sherds, plant material, branches and sand with the earth. Ditches up to fifty metres wide, frequently filled with water, and even a double ring of circuit wall were other techniques designed to ensure a city could withstand set on long enough for a relieving forcefulness to arrive from elsewhere.

The Great Wall of China

Not only cities but land frontiers were protected past high walls and watchtowers. The earliest may have been in the north from the 8th century BCE but the practice became a common one in the Warring States Menses when many different powerful states vied for control of People's republic of china. Almost of these structures were dismantled by the victor state, what would go the Qin Dynasty from 221 BCE, but i wall was profoundly expanded to get the Cracking Wall of People's republic of china. Extended again by subsequent dynasties, the wall would somewhen stretch some 5,000 km from Gansu province in the due east to the Liaodong peninsula. The construction was not continuous but it did, for several centuries, assist protect People's republic of china's northern frontier against invasion from nomadic steppe tribes.

Organisation & Strategies

China'southward history is an extremely long one and each fourth dimension period and dynasty saw its own practices and innovations in warfare. Still, some themes run through the history of warfare in China. Officers were oftentimes professionals (although they commonly inherited their status), ordinary troops were conscripts or captured soldiers; convicts could besides be pressed into service. In that location were also volunteers, typically young men from noble families who joined as cavalrymen looking for take chances and glory. The organisation of an army in the field into iii divisions had a long tradition. So, also, did the five-man unit, typically applied to infantry where squads were composed of ii archers and iii spearmen. By the Warring States period, an regular army was typically divided into five divisions, each represented by a flag which denoted its function:

- Red Bird - Vanguard

- Dark-green Dragon - Left Wing

- White Tiger - Right Wing

- Black Tortoise - Rear Baby-sit

- Neat Bear Constellation - Commander & Babysitter

When the crossbow became more common troops skilful with that weapon frequently formed an elite corps and other specific units were used every bit shock troops to help out where needed or confuse the enemy. Equally already noted above, archers and cavalry protected the flanks of heavier infantry and chariots, when used, could fulfill the same function or bring up the rear. Such positions, which are described as ideals in the military machine treatises, are confirmed by the Terracotta Army of Shi Huangti. Flags, unit of measurement banners, drums and bells were used on the battlefield to better organise troops and deploy them in the manner the commander wished.

Supporting the soldiers were dedicated officers responsible for logistics and supplying the army with the necessary food (millet, wheat and rice), h2o, firewood, fodder, equipment and shelter they needed while on campaign. Fabric was transported by river whenever possible and if not, on ox carts, horses and even wheelbarrows from the Han menstruation onward. From the Warring States Period, and specially the Han period, portions of armies were set the task of farming then every bit to acquire the necessary vitals that foraging, confiscation from locals or capture from the enemy could not supply. The institution of garrisons with their own food production and improvements in supply roads and canals also went a long way to lengthening the fourth dimension an army could finer stay in the field.

Full-on infantry battles, cavalry skirmishes, reconnaissance, espionage, subterfuge, and deadfall were all nowadays in Chinese warfare. Much was made of gentlemanly etiquette in war during the Shang and Zhou periods but this was likely an invention of afterward writers or at all-time an exaggeration. Certainly, when warfare became more than mobile and the stakes fabricated college from the 4th century BCE, a commander was expected to win with and by any means at his disposal.

One final theme which runs through much of Communist china'due south history is the apply of expert diviners who could written report omens, find the move and position of angelic bodies, gauge the meaning of natural phenomena and consult calendars all in order to make up one's mind the virtually auspicious time and identify to engage in warfare. Without these considerations, it was believed, the best weapons, men and tactics would not be enough to bring last victory.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Chinese_Warfare/